Robust fit

This article is roughly a follow-up to this one.

scipy.optimize.least_squares

There are several methods for robust fitting. Let’s start with this function from scipy.

First, let’s look at this example from the scipy cookbook.

This example fits a sine function:

def generate_data(t, A, sigma, omega, noise=0, n_outliers=0, random_state=0):

y = A * np.exp(-sigma * t) * np.sin(omega * t)

rnd = np.random.RandomState(random_state)

error = noise * rnd.randn(t.size)

outliers = rnd.randint(0, t.size, n_outliers)

error[outliers] *= 35

return y + errorDefine model parameters:

A = 2

sigma = 0.1

omega = 0.1 * 2 * np.pi

x_true = np.array([A, sigma, omega])

noise = 0.1

t_min = 0

t_max = 30Put three outliers in the fitting dataset:

t_train = np.linspace(t_min, t_max, 30)

y_train = generate_data(t_train, A, sigma, omega, noise=noise, n_outliers=4)Define the loss function:

def fun(x, t, y):

return x[0] * np.exp(-x[1] * t) * np.sin(x[2] * t) - yThe rest is standard procedure:

x0 = np.ones(3)

from scipy.optimize import least_squares

res_lsq = least_squares(fun, x0, args=(t_train, y_train))

res_robust = least_squares(fun, x0, loss='soft_l1', f_scale=0.1, args=(t_train, y_train))

t_test = np.linspace(t_min, t_max, 300)

y_test = generate_data(t_test, A, sigma, omega)

y_lsq = generate_data(t_test, *res_lsq.x)

y_robust = generate_data(t_test, *res_robust.x)

plt.plot(t_train, y_train, 'o', label='data')

plt.plot(t_test, y_test, label='true')

plt.plot(t_test, y_lsq, label='lsq')

plt.plot(t_test, y_robust, label='robust lsq')

plt.xlabel('$t$')

plt.ylabel('$y$')

plt.legend();You can clearly see that the robust lsq result is obviously closer to the true line.

Here we only used soft_l1. There are several other options in least_squares:

loss str or callable, optional

Determines the loss function. The following keyword values are allowed:

- ‘linear’ (default) :

rho(z) = z. Gives a standard least-squares problem.- ‘soft_l1’ :

rho(z) = 2 * ((1 + z)**0.5 - 1). The smooth approximation of l1 (absolute value) loss. Usually a good choice for robust least squares.- ‘huber’ :

rho(z) = z if z <= 1 else 2*z**0.5 - 1. Works similarly to ‘soft_l1’.- ‘cauchy’ :

rho(z) = ln(1 + z). Severely weakens outliers influence, but may cause difficulties in optimization process.- ‘arctan’ :

rho(z) = arctan(z). Limits a maximum loss on a single residual, has properties similar to ‘cauchy’.

The annoying thing is that this time it’s not as convenient as the curve_fit function.

I still have to manually write a cost function.

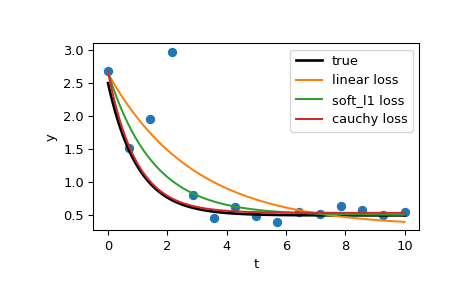

Another Example

This example comes from here.

Thanks to this example for teaching me how to write a cost function.

Define the model function as y = a + b * exp(c * t), where t is a predictor variable, y is an observation and a, b, c are parameters to estimate.

First, define the function which generates the data with noise and outliers, define the model parameters, and generate data:

>>> def gen_data(t, a, b, c, noise=0, n_outliers=0, random_state=0):

... y = a + b * np.exp(t * c)

...

... rnd = np.random.RandomState(random_state)

... error = noise * rnd.randn(t.size)

... outliers = rnd.randint(0, t.size, n_outliers)

... error[outliers] *= 10

...

... return y + error

...

>>> a = 0.5

>>> b = 2.0

>>> c = -1

>>> t_min = 0

>>> t_max = 10

>>> n_points = 15

...

>>> t_train = np.linspace(t_min, t_max, n_points)

>>> y_train = gen_data(t_train, a, b, c, noise=0.1, n_outliers=3)Define function for computing residuals and initial estimate of parameters.

>>> def fun(x, t, y):

... return x[0] + x[1] * np.exp(x[2] * t) - y

...

>>> x0 = np.array([1.0, 1.0, 0.0])NOTE: x0, x1, x2 correspond to a, b, c; and t is what we always treat as x.

Compute a standard least-squares solution:

>>> res_lsq = least_squares(fun, x0, args=(t_train, y_train))Now compute two solutions with two different robust loss functions. The parameter f_scale is set to 0.1, meaning that inlier residuals should not significantly exceed 0.1 (the noise level used).

>>> res_soft_l1 = least_squares(fun, x0, loss='soft_l1', f_scale=0.1,

... args=(t_train, y_train))

>>> res_log = least_squares(fun, x0, loss='cauchy', f_scale=0.1,

... args=(t_train, y_train))t_test = np.linspace(t_min, t_max, n_points * 10)

>>> y_true = gen_data(t_test, a, b, c)

>>> y_lsq = gen_data(t_test, *res_lsq.x)

>>> y_soft_l1 = gen_data(t_test, *res_soft_l1.x)

>>> y_log = gen_data(t_test, *res_log.x)

...

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

>>> plt.plot(t_train, y_train, 'o')

>>> plt.plot(t_test, y_true, 'k', linewidth=2, label='true')

>>> plt.plot(t_test, y_lsq, label='linear loss')

>>> plt.plot(t_test, y_soft_l1, label='soft_l1 loss')

>>> plt.plot(t_test, y_log, label='cauchy loss')

>>> plt.xlabel("t")

>>> plt.ylabel("y")

>>> plt.legend()

>>> plt.show()

This example also has a section on solving complex optimization problems at the end, which is really impressive.

scikit learn

This is largely similar:

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn.linear_model import (

LinearRegression, TheilSenRegressor, RANSACRegressor, HuberRegressor)

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline

np.random.seed(42)

X = np.random.normal(size=400)

y = np.sin(X)

# Make sure that it X is 2D

X = X[:, np.newaxis]

X_test = np.random.normal(size=200)

y_test = np.sin(X_test)

X_test = X_test[:, np.newaxis]

y_errors = y.copy()

y_errors[::3] = 3

X_errors = X.copy()

X_errors[::3] = 3

y_errors_large = y.copy()

y_errors_large[::3] = 10

X_errors_large = X.copy()

X_errors_large[::3] = 10estimators = [('OLS', LinearRegression()),

('Theil-Sen', TheilSenRegressor(random_state=42)),

('RANSAC', RANSACRegressor(random_state=42)),

('HuberRegressor', HuberRegressor())]

colors = {'OLS': 'turquoise', 'Theil-Sen': 'gold', 'RANSAC': 'lightgreen', 'HuberRegressor': 'black'}

linestyle = {'OLS': '-', 'Theil-Sen': '-.', 'RANSAC': '--', 'HuberRegressor': '--'}

lw = 3

x_plot = np.linspace(X.min(), X.max())

for title, this_X, this_y in [

('Modeling Errors Only', X, y),

('Corrupt X, Small Deviants', X_errors, y),

('Corrupt y, Small Deviants', X, y_errors),

('Corrupt X, Large Deviants', X_errors_large, y),

('Corrupt y, Large Deviants', X, y_errors_large)]:

plt.figure(figsize=(5, 4))

plt.plot(this_X[:, 0], this_y, 'b+')

for name, estimator in estimators:

model = make_pipeline(PolynomialFeatures(3), estimator)

model.fit(this_X, this_y)

mse = mean_squared_error(model.predict(X_test), y_test)

y_plot = model.predict(x_plot[:, np.newaxis])

plt.plot(x_plot, y_plot, color=colors[name], linestyle=linestyle[name],

linewidth=lw, label='%s: error = %.3f' % (name, mse))

legend_title = 'Error of Mean\nAbsolute Deviation\nto Non-corrupt Data'

legend = plt.legend(loc='upper right', frameon=False, title=legend_title,

prop=dict(size='x-small'))

plt.xlim(-4, 10.2)

plt.ylim(-2, 10.2)

plt.title(title)

plt.show()The PolynomialFeatures(3) means it can fit polynomials from 0th order to 3rd order.

Robust fitting is demoed in different situations:

- No measurement errors, only modelling errors (fitting a sine with a polynomial)

- Measurement errors in X

- Measurement errors in y

The median absolute deviation to non corrupt new data is used to judge the quality of the prediction.

What we can see that:

- RANSAC is good for strong outliers in the y direction

- TheilSen is good for small outliers, both in direction X and y, but has a break point above which it performs worse than OLS.

- The scores of HuberRegressor may not be compared directly to both TheilSen and RANSAC because it does not attempt to completely filter the outliers but lessen their effect.

iterative bi-square method

What I actually wanted to find most was this, which comes from this paper.

But I couldn’t find a Python package for it anywhere.

Ah, it’s forcing me to switch to R again.